Ahmad Shamlou

بهمن ۱, ۱۳۹۵

About a Fish & a Cat (Asbi Square): A Short Story

بهمن ۱۴, ۱۳۹۵Forough Farrokhzad is undoubtedly one of the most prominent among the Iranian woman poets in the history of Persian literature. Her significant achievements in poetry and film production during her relatively short life and her unexpected death have made her an enigmatic and almost legendary person. Her avant-garde poems were both praised and criticized during her life. Half a century after her death, she is still one of the most read and acclaimed Iranian poets; as well as continuing to be one of the most controversial people in Persian literature.

When thinking about Forough Farrokhzad, one is always faced with the question: “What makes her so enigmatic and legendary?” Is it because of her powerful poems? Well, she was not the only Iranian poet who wrote good poems. Is it because of her activities in film production? But she was not the only Iranian filmmaker who gained international praise. Or is it because of her independent life as a female intellectual in a male-dominated society that has made her a role model for different generations of Iranian women? This essay aims to give a summary of Forough Farrokhzad’s life and works and to shed light on some critical issues in her life that are of interest and importance for both Iranian and international readers.

“I do not know what arriving is,

but without a doubt, there is a destination

towards which my whole being flows.”-Forough Farrokhzad

Forough Farrokhzad in a video interview with Bernardo Bertolucci, the Italian Filmmaker and poet, in 1964.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Early Life

Forough-Ozzaman Farrokhzad, the 3rd of 7 children of Mohammad Farrokhzad, an army officer, and Batul Vaziry-Tabar, a housewife, was born on December 28th, ۱۹۳۴[۱] in Tehran. Although they were considered a well-to-do family, Forough’s father as a person with military background raised his children according to military disciplines; the children were treated harshly, and they had to work from early adolescence to gain their pocket money. In an interview Forough said:

“Since childhood our father made us acquainted with what is known as ‘hardship.’ We slept and grew up in military blankets, whereas in our house fine and soft blankets could and can be found. Our father brought us up according to his especial norms.” (The Eternal Sunset, 68)

Her father’s attitude towards disciplining his children may seem harsh, but this training since childhood may be a reason for Forough’s independent and self-reliant personality in her adulthood. Although a military man, her father was also a man of culture having a small library at home, which prompted Forough’s early readings.

Forough started writing poetry at the young age of 14 while attending high school. Her early poems were in ghazal form _a classic Persian poetic form with a set of strict rhythmic and rhyming rules. She wrote these poems casually with no intention of publishing them, and indeed they were never published because she destroyed them almost as soon as they were done since she was scared of her father’s reaction towards her writing poetry.

In 1949 she entered an art school for girls where she learned painting and embroidery, which were popular skills for girls from the middle class when it was not common for them to attend university and receive an academic education.

Forugh’s family: (standing) her father, Mohammad Farrokhzad. (sitting on the upper step) her mother, Batul Vaziry-Tabar; her younger brother, Fereydun; her older sister, Puran. (sitting on the lower step) her older brother, Amir-Masoud; and Forugh herself.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Marriage

At the age of 16, Forough fell in love with Parviz Shapur, a neighbor and a distant relative 15 years her senior. It is not uncommon in Iranian culture for girls to get married at a young age, despite this, her parents were against her getting married this young, but finally succumbed to her will after her insistence. Therefore, they got married in 1950; a marriage about which a few years later she said: “That absurd love and marriage at the age of 16 disturbed the base of my future life” (The Eternal Sunset, 60).

Soon after a simple marriage ceremony, she had to leave Tehran to settle in the city of Ahvaz in the south of Iran because of her husband’s occupation. This migration put an end to Forough’s formal education. She never received any further academic education during her life.

Despite her new chores as a housewife, she continued writing poetry, still as a hobby:

“It was a time when I regarded poetry as a sort of entertainment and casual activity. After getting rid of cutting vegetables for dinner, I would scratch my head and say ‘alright, now let’s go and write a poem . . .” (Cited in Like Nobody Else, 15).

Forough Farrokhzad, Kamyar, Parviz Shapur

The Sin by Forough Farrokhzad

Later she thought of having her poems published, therefore she took a trip to Tehran, and went to a literary magazine named Roshanfekr whose poetry section was managed by Fereydun Moshiri, a prominent poet in 1950s, and offered her first poem named Gonah (The Sin) for publishing. The poem had a romantic-erotic theme which was not very uncommon in that era, but the fact that a young woman wrote it made it a controversial one. Of that incident Moshiri said in an interview with Nasser Saffarian:

“It was very amazing for me. The person who was sitting in front of me looked more like a girl rather than a woman. [But] she had written: ‘I made a sin, a sin rich in pleasure / In a bosom hot like fire’” (Verses of Sigh, 269)

The publication of this poem caused a lot of controversy among the readers of the magazine. The fanatics would blame Roshanfekr for “writing the explanation of a woman’s sexual encounter” (Verses of Sigh, 270), but the intellectuals and students would praise them and demand more poems to be published. Anyhow, the publication of this poem and the poems published afterward caused both sudden fame for Forough and an increase in the circulation rate of Roshanfekr which the managers looked forward to.

This fame and the controversies were not something that Forough’s father and husband were looking forward to. Her husband, although he was himself a man of letters, did not approve of her intellectual activities, her controversial poems, and her trips to Tehran to publish her works. Nevertheless, in the following year, in 1952, she compiled a collection of her poems under the title of Asir (The Captive) and sent them to a publisher. In this stage of her life as a poet, she was inspired by Nader Naderpur, Fereydun Moshiri, two famous figures in Persian poetry in the 1950s. All of the poems in this volume had similar romantic, erotic, and sometimes feminist themes and were written in a poetic form called Chaharpareh, which was a favorite poetic form during the 1950s in Iran. Chaharpareh was created by some modulation in Iranian classic poetic forms: the poem was broken into sections of 4 rhythmic lines, every even lines end-rhymed. Chaharpareh was very popular before Nima Youshij’s Nimaic form, and Ahmad Shamlou’s freeform She’r-e Sepid gaining prominence in Iran. Although this volume is not considered a major work compared to Forough’s later works it received positive feedback from the readers and was republished in the following years.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Separation

In the very year, just a few weeks after the publication of her first poetry book, she gave birth to her only child, a son named Kamyar. As one would expect, now as a mother her chores at home multiplied. She had less time to focus on her poetry, something that was not a casual activity anymore, and had become of great importance for her, as she said:

“Now poetry is a serious issue for me. It is like a responsibility that I feel before myself. It is like an answer that I must give to my own life. I respect poetry like a religious person respecting his creed.” (Cited in The Eternal Sunset, 20)

Despite this, she continued writing more poems and publishing them in different literary magazines. As she was gaining more fame, magazines would ask her for interviews. Obviously, Parviz could not tolerate this. Forough was under so much pressure to decide between her life as a housewife, or a poet. Finally, in 1955 they agreed on a separation. This separation was tough for both of them and left its permanent mark on them. Never again Parviz got married, and Forough who was denied from visitation with her child had a tough time. Indeed, she could never fully recover from losing her beloved son. Forough and Parviz although separated, did not hate each other; a possible clue to this is Forough dedicating her next poetry volume named Divar (The Wall) to Parviz. But Parviz’s family blamed her for their separation and denied her occasional visiting of her child. They had even told Kamyar not to go near Forough or speak to her at times when she went to his school to visit him. Not talking to or seeing each other was very tragic for both the mother and the child.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Trips Abroad

The trauma of the separation and losing her child and the pressure from her own family who also blamed her for the divorce gave her a nervous breakdown for which she had to be hospitalized in a mental hospital for a few months.

Released from the hospital and now a divorcée she went to her father’s house, but she could not stay there for a long time because her father still blamed her for the divorce, and her writing poetry. So, she had to rent a small place in Tehran after staying at a friend’s house for a few weeks. She did not have any job, and she refused to receive pension form her ex-husband, so she had to look for a job and to struggle with poverty. In a letter to her father after leaving his house, she explained with a painful tone:

“My biggest pain is that you never knew me, and you never wanted to know me. Perhaps you still think of me as a foolish woman with silly ideas … but I wish I was like that; then I could be fortunate. I would be happy to live in a small house with a husband who wished to remain a low-rank state clerk for the rest of his life, and who was scared of any responsibility and risk for promotion. And I could be happy to wear fancy clothes and go to parties, and chatter with neighbors, and fight with my mother in law, and in short be satisfied with every cheap and trivial activity one can do. I would have never known a bigger and more beautiful world, and I would have had to squirm in my little dim cocoon like a larva and just pass my life away! But I could have not, and I cannot live like that.” (The Eternal Sunset, 108)

Forough Farrokhzad and her brother, Amir-Masoud, in Germany

She published her second poetry book, Divar (The Wall) in 1956, which had similar themes to her previous book. In the same year, she participated in a play called “Blood Wedding” written by Gabriel Garcia Lorca, translated by Ahmad Shamlou, and meant to be directed by Ahmad Shamlou himself. But due to some complications, this project could not go beyond rehearsal. Some backstage pictures of this play remain, but it never went on stage.

In the very year to make a change in her life after the traumatic separation, and also to escape from the unfair criticisms in the magazines and literary circles who would make a judgment about herself and her lifestyle rather than her poems and her literary skills, she traveled to Italy. About these criticisms she had written earlier in a letter:

“. . . I willingly accept fair criticisms, but not a self-righteous and prejudicious criticism which is only made to demean and defeat the subject. . . . But despite all of these I will not surrender. I will not be defeated, and I will bear everything with absolute self-possession, like what I have always done.” (The Eternal Sunset, 57)

During her seven month stay in Italy, she worked on different jobs from an extra in Italian movies, to dubbing films into Persian in Iranian studios in Italy. The memoirs of her travel to Italy was published in an Iranian magazine after she went back to Iran in the following year. Before that, she took another trip to West Germany invited by her older brother Amir-Masoud, who worked and lived there. She learned some German and read German poetry during her stay. With the help of her bother, she translated a selection of poem by 100 contemporary German poets, which did not complete during her lifetime. But it was later completed by her brother and was published posthumously in 1998, under the title Marg-e Man Ruzi… (My Death Someday…).

Missing her country, she decided to go back to Iran in the summer of 1957, while she could stay in Germany for an unlimited time.

Golestan Film

Back in Tehran, in 1958, at the age of 24, she published her 3rd poetry book, Osyan (The Rebel), which she had compiled during the previous two years. This volume was not much different in form from the last 2, but one could see a slight change in content as the poet had aged and had gained more knowledge and experience. But this change was not as significant compared to the second phase of her poetry which began with the publishing of her next book in 1964. Regarding this book and the previous ones she said:

“I was not fully formed yet; I hadn’t yet found my own style, language, and intellectual conception. I was in a small and bounded atmosphere which we call ‘family life.’ But then suddenly I got rid of all of those. I changed my surroundings; I mean it changed naturally and unintentionally. Divar and Osyan were, in fact, a hopeless struggling between two stages of life; final gasps before a kind of salvation.” (The Eternal Sunset, 164)

In the same year, she was introduced to Golestan Film Organization, a film production company managed by Ebrahim Golestan, a famous Iranian director, writer, and translator. Her first occupation in Golestan Film was a simple job as a secretary. But soon when Mr. Golestan realized she had a talent in film production, he gave her a promotion within the company as an editor. To be able to perform her job she was sent to Britain to pass a course on film editing. After a few months of training, she went back to work on her first film editing project, named Yek Atash (A Fire), a documentary about one of the Iranian oil wells in the south of Iran catching fire.

In 1960, she again took her chance to act in 2 more plays, but both of them again failed to be performed on the stage due to different complications. In the next year, she acted in a short film named Khastegari (Suiting), directed by Ebrahim Golestan; a film, as the name suggests, on suiting and marriage ceremonies in Iran, ordered by a Canadian film institution.

In Golestan’s next project, Ab o Garma (Water & Heath), which was a two episodic documentary, Forough accompanied Golestan during the shooting. When Golestan learned that she was interested and had talent in film direction, he let Forough lead the crew during the shooting of the second episode of the film _she edited both episodes.

Forough Farrokhzad during the shooting of Khane Siah Ast

The House is Black by Forough Farrokhzad

After another educational trip to Britain in 1961, and after producing two advertisements for Keyhan Newspaper, and Pars Oil Company _now following filmmaking professionally_ she started her most significant and celebrated film project:

Golestan Film received an order to make a documentary about a leper colony near the city of Tabriz in the north-west of Iran from a nonprofit organization to raise consciousness about leprous people. Golestan agreed to make the film, and send Forough and her film production crew to Tabriz. Forough and her filming crew stayed for 12 days in Bababaghi leper camp to shoot her short documentary named Khaneh Siah Ast (The House is Black), which gained critics’ praise after its screening in Iran and worldwide.

Watch below entire footage of Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black:

Khanneh Siah Ast is probably the best Iranian short film ever. The film verges on a documentary about lepers and leprosy that is meant to raise viewers’ consciousness, and a poetic-philosophic film. It is an excellent fusion of poetry and cinema. The film starts with Forough narrating her own poems over the footage of a group of lepers under treatment in Bababaghi colony and interrupted by Mr. Golestan’s voice citing some facts about lepers and leprosy. The poems and the pictures have a deep and powerful correlation, to the extent that it is not clear if the poems are composed inspired by the footage or vice versa. We expect to see ugly pictures of leprous people, but Forough’s camera makes us see beauty in them, like them, and empathize with them. In the end, the film makes us wonder about our own lives, and think “are we not similar to lepers in a leper colony in a way or another? Are our lives any different from them, except for a few trivialities that we have crowded our lives with?”

Shots from Khaneh Siah Ast

Khaneh Siah Ast won the prize for the best short documentary among 65 competitors at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, one of the most important festivals for short films held in the city of Oberhausen in Germany, in the year 1964.

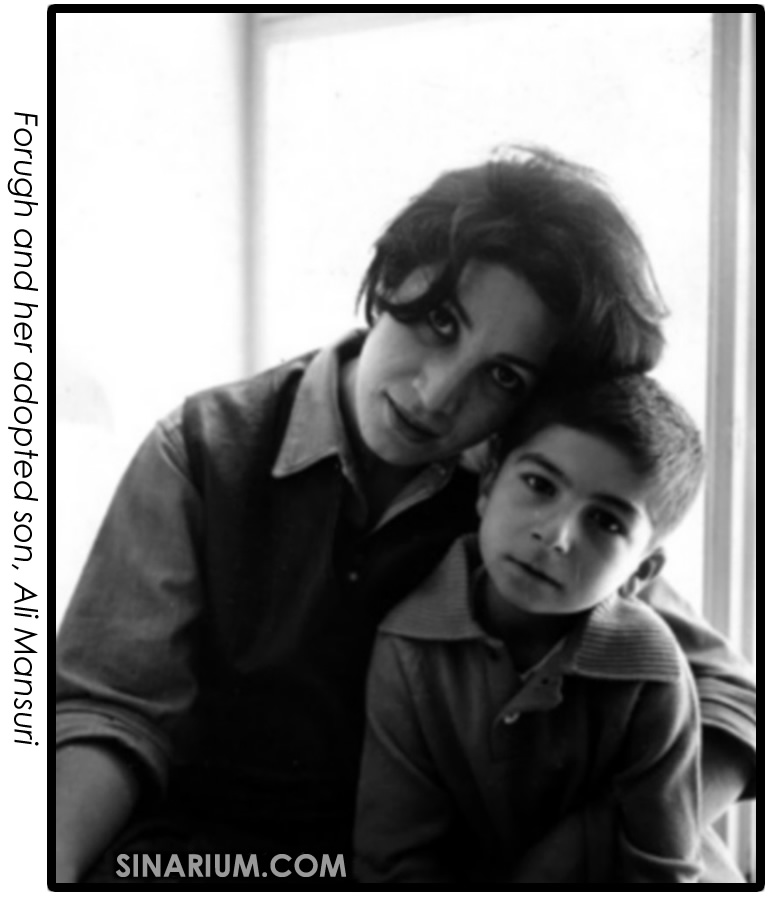

During the time of shooting the film at the leper camp, Forough met a boy named Hossein, son of a leprous couple, who reminded her of her own son, Kamyar. When she was returning from the camp she adopted the boy and took him to Tehran to live with her. This incident could have relieved her pain of losing her son which had been troubling her for years. Hossein stayed with Forough until her death, and after that, until the age of maturity, he stayed with Forough’s mother.

Forugh and her adopted son, Ali Mansuri

Forough Farrokhzad’s Rebirth

Right after the release of her film, Forough published a collection of poems that she wrote during the past few years when she was active as a filmmaker, under the title of Tavalodi Digar (Rebirth), which began her second phase of life as a poet. She believed that she indeed was reborn after the publication of this book. This statement seems to be right when we compare it to her previous poetic endeavors; her poems were richer in content and form. One could already sense a change in Forough’s poetry beginning from the very poems narrated on Khaneh Siah Ast. We can see a significant shift in her worldview, style, tone, and themes. Instead of the previous mostly romantic and personal poems, these poems have broader philosophical and social concepts which could be perceived by many people regardless of their gender, nationality and social standing. Besides, she used different literary elements that were innovative in Persian literature. These novelties until today have inspired many Iranian poets. Perhaps if it was not due to this poetry book, she could never gain so much prominence in the Persian literature. Regarding this poetry book, and her poetry in general, she said:

“I regret publishing Asir, Divar, and Osyan. I regret why I didn’t begin with Tavalodi Digar. . . . In Asir, Divar, and Osyan, I was simply recounting the external world; poetry hadn’t yet gone through my being . . . But then poetry was enrooted in me, and that was how the themes of poetry became different for me. I didn’t use poetry anymore to express a simple feeling about myself, but as poetry was sinking in me, I grew vaster, and I discovered new worlds.” (The Eternal Sunset, 195)

In this stage, she was inspired by two renowned Iranian poets, Nima Youshij, the innovator of Nimaic form, and Ahmad Shamlou who is famous for his non-rhythmic “white poems.” Although Forough always supported using rhythm in poetry, and she never put rhythm aside, under the influence of the poets mentioned above, she adopted the Nimaic form in her later book and used a milder rhythm in her poems. Her remaining poems composed after Tavalodi Digar are even closer to non-rhythmic free verse. Forough was familiar with western poetry and literary schools, for example, she had read works of T. S. Eliot and Paul Éluard which possibly affected her works during this stage.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Final Years & Death

Forough did not suffer from chronic depression, but she sometimes experienced brief moments of great sorrow and sadness which led to her two unsuccessful suicide attempts in the last few years of her life. Like any other intellectual living in this world, she had a “common pain” which denied her seeing the world as a total bliss. Her marriage and losing custody of her child were the greatest traumatic experiences she underwent. Also during the years of her activity with Golestan Film, she formed a close, and supposedly amorous relationship with Ebrahim Golestan, a married man, and father of a son and a daughter. This relationship obviously could not continue, and on top of all the pressure that it was putting on Golestan family, it was stroking a new round of rumors around Forough among people who were hungry for every triviality to debase her. As a woman living in a male-dominated society, she had to endure a lot of discrimination. During her short life, she received a lot of negative, unjust, and usually personal criticism usually from men who considered her an undesirable figure in the Iranian intellectual circles. She wrote in a letter to Golestan:

“What a strange world it is. I do not meddle with anybody, but this non-hostility and my keeping myself to myself make people even more curious about me. I do not know how to deal with people.” (The Eternal Sunset, 63)

Ebrahim Golestan & Forough Farrokhzad

After the publication of Tavalodi Digar Forough was at the top of her professional success. The last few years leading to her death were her most active years. On top of her activities at Golestan Film, and writing poems, she became more interested in painting and drawing. Also, she could at last act in a play: ۶ Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello, directed by Pari Saberi. She also had sporadic social and political activities and supported students’ protests against the Shah’s policies, which led to her temporary confinement in the police lockup. Thankfully this activism did not result in any serious problems for her.

The poems she wrote and published in literary journals, which were posthumously published in a volume titled Iman Biavarim be Aghaz-e Fasl-e Sard (Let Us Believe in the Coming of the Cold Season) proved to be even more successful than her previous works. Alas, this sudden eruption in her poetic talent was extinguished by her unexpected and untimely death in a car accident when she was driving on to her office, on February 13th, ۱۹۶۷. Two days later she was buried in Zahir-Oddoleh graveyard in Tehran while hundreds of people, including the most famous literary faces, gathered to mourn this significant loss. She was 32 years old when she died.

Forough Farrokhzad’s Legacy

Commit the Flight to memory,

for the Bird is mortal– Forough

At the time of her death, Forough Farrokhzad was already a prominent person, at least among literary and intellectual circles in Iran, but it was years after her death that her works began to be reevaluated by generations to come. Today Forough stands shoulder to shoulder with Iran’s most famous people of all time. Her importance is to the extent that Reza Baraheni, Iranian poet and critic, claims that “Forough Farrokhzad is the greatest woman in Iranian history” (Like Nobody Else, 61).

Many people may share the same point of view with Mr. Baraheni when they consider the context in which Forough was born and her achievements despite this prejudicious context. It was a context of living in a male-dominated society in which women were hidden either under the veil or lived most of their lives inside the walls of houses with hardly any social presence. Even though there were a few female poets before Forough, they were either silenced by jealous fathers, brothers, and husbands or had to speak with a masculinized voice about a masculine world. Forough was the first female poet who spoke of and about women and women’s world. Disregarding some of her poems in the first phase of her life, she neither took a radical feminist view when dealing with men nor did she become masculinized in her second phase of poetry when she wrote about the common pains of the humanity. When reading her poems, one can hear a feminine voice talking of thoughts shared by all human beings.

Her professional success aside, her lifestyle also makes her a role model for Iranian women. Forough Farrokhzad lived an independent life without relying on any men for support. She praised women’s subjectivity and freedom. She was against the Middle Eastern concept of veiled women at home, but on the other hand, she did not go for the western concept of women as beautiful dolls. Forough Farrokhzad was a living poem, defining the immortal beauty of a divine woman by living her truth.

“I wish I could die and rise again to see the world has become different. The world is not so much cruel, and people have lost their general miserliness, and nobody marks his house with fences.”

Footnote

[۱] The birth date of Forough Farrokhzad was also mentioned as January 4th 1935 by some sources including “In an Eternal Sunset” by Behrouz Jalali, and “Forough in the Garden of Memories” an essay by Mahasti Shahrokhi; but in “The Verses of Sigh” by Nasser Saffarian, the given date is December 28th, ۱۹۳۴. The latter source seems to more reliable.

Sources

The Verses of Sigh (Original title: آیه های آه), Nasser Saffarian, Tehran: Ruznegar, 2002.

In an The Eternal Sunset: Collection of written works of Forough Farrokhzad (Original title: در غروبی ابدی: مجموعه ی آثار منثور فروغ فرخزاد), Behruz Jalali, Tehran: Morvarid, 1997.

Someone who is like Nobody Else: About Forough Farrokhzad (Original title: کسی که مثل هیچ کس نیست: درباره ی فروغ فرخزاد), Puran Farrokhzad, Tehran: Caravan, 2001.

I wrote this essay when I was an undergraduate English literature student at the University of Mazandaran, Iran. It was first published in Derafsh-e Mehr, a literary student journal that I published at the University. You can still download and read the digital issues on Derafsh-e Mehr weblog as well as on Derafsh-e Mehr page on Sinarium.

کارشناس زبان و ادبیات انگلیسی | کارشناس ارشد سینما | مدیر ویسایت سیناریوم |

از نوشتن و ترجمه لذت می برم _به خصوص اگر راجع به سینما و ادبیات باشه |

سیناریوم رو زمستون ۹۶ درست کردم و تابستون ۹۷ یک فروشگاه اینترنتی یادگاری های سینمایی هم بهش اضافه کردم | سیناریوم اول برام یه تفریح بود اما الان برام تبدیل شده به یه «خود دیگر»!

4 دیدگاه

Thank you for posting this wonderful biography. I enjoyed it very much.

Thanks a lot for your reading it and commenting.

Thankyou very much for this information

🌹❤️